The Legacy of the Euros 2022

“The legacy of tonight is a change in society.”

Lionesses Captain Leah Williamson 31.07.22

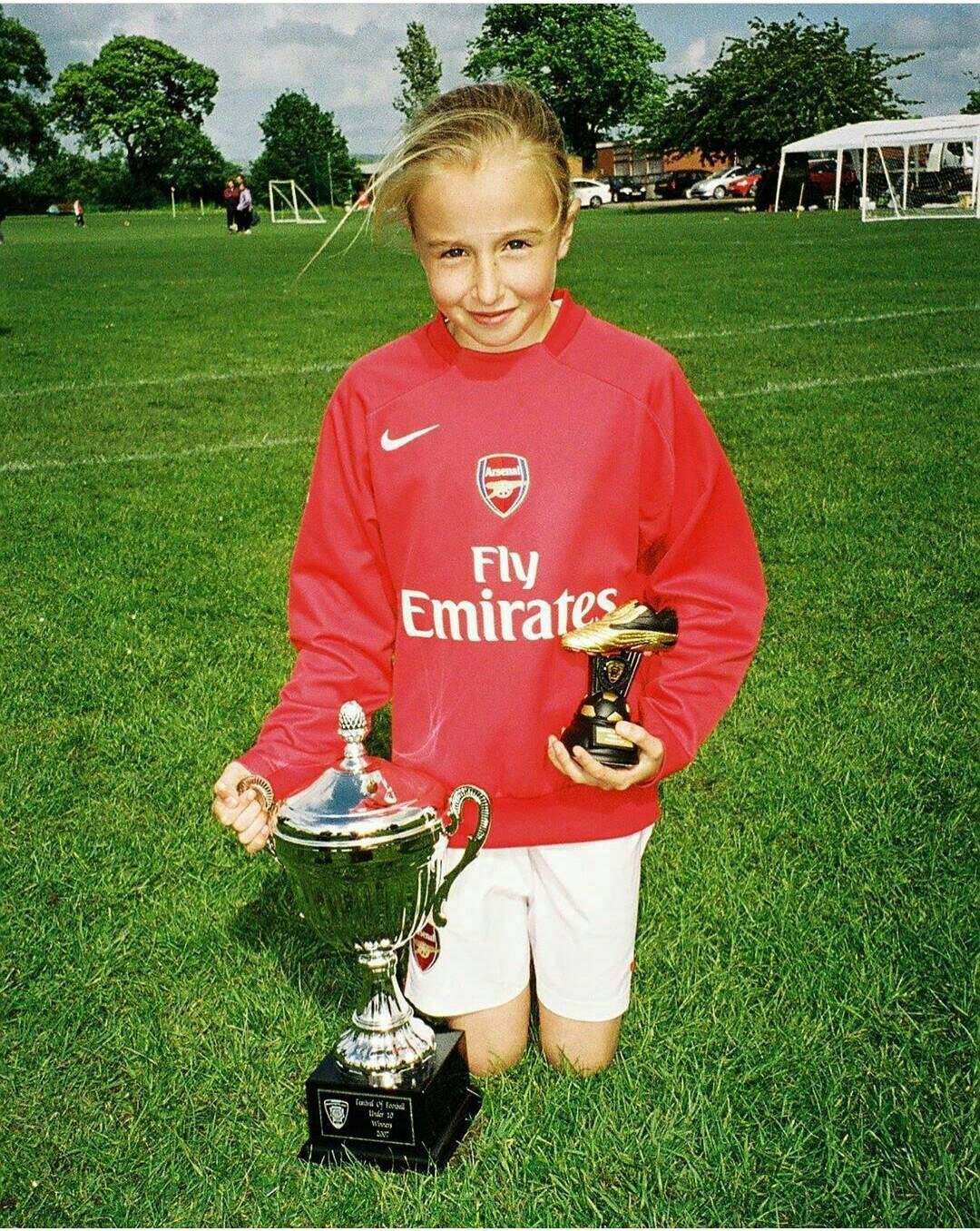

It’s a beautiful summer’s evening at Oppidan Camp and none of the girls are playing football. The boys are - they’re charging around trying to take each other’s heads off, shouting and screaming the names of their favourite players as they try to emulate them with heroic actions: last ditch saves, magical passes and stunning strikes.

The girls aren’t.

And while the boys are talking about Messi and Ronaldo, the (vast majority of) girls seem neither to care about these men or relate in any way to them. Do they mirror their actions? Can they see a future in football? No and no - this professional pathway has never been modelled for them to see; their aspirations implicit since birth and informed to them at government, local or at family level.

When Leah Williamson lifted a curved silver trophy in northwest London on Sunday night, she triggered what she called “a change in society;” what everyone hopes will be a sea-change in our collective investment of women’s sport.

As Ian Wright said after England’s semi-final defeat of Sweden: “if girls aren’t allowed to play football just like the boys can in their PE after this tournament, then what are we doing?”

So, what should we do?

We should remain alert to the implicitly gendered ways in which children’s personal development is championed in schools.

We must review our students’ scores in our character assessment framework to eliminate our team’s own hidden biases.

We should recruit more professional sportswomen like the amazing Maddy Nutt so that young women we work with can see a marked path in front of them.

Individual mentoring sessions with our team must develop and inspire the same aspirations irrespective of gender.

We must reflect on the language in classrooms to ensure parity of expectation – the use of words like “bossy” or “sassy” to represent “confident” or “assertive” entrench negative stereotypes, rather than empowering girls.

More broadly, we must explicitly model to our schools an approach that is powerful and engaging, irrespective of gender difference. The way we parent and the biases of our generation inform the ways we teach and direct; automatic grouping of boys and girls in PE or a difference in the uniform that boys and girls wear to play sport are two examples – at one school the girls ran an internal campaign to allow them to wear trousers instead of skirts to play cricket. “Implicit semantics – “good girl” - can be binary; continual assessment of our language must at the heart of everything we do.

Like we can’t expect all boys to do so, similarly we can’t expect all young girls to pick up a ball and kick it across a meadow all the way to Wembley. But now the Lionesses have proven that anything is possible, we should be tough on ourselves to create a system that shows them just that, a system that, by camp next year, allows girls and boys to play football together.